Excerpt from Chapter 6

Deciding to Learn: The Power of Metacognition

Welcome back to the sixth and final installment of our six-part blog series! If you're just joining us, be sure to catch up on our previous posts. If you have a student or child that has trouble monitoring their progress and assessing their learning, you won’t want to miss this post! Metacognition is the ability to observe one's actions and results and then make modifications in pursuit of a goal. It includes having an awareness of one's strengths and weaknesses. What does Metacognition look like in practice? If a students realizes that homework won't get done unless task initiation challenges are overcome and it's started right after school, then that students is practicing metacognition!

Below, get a sneak peek with an exclusive excerpt from ©Your Kid’s Gonna Be Okay: Building the Executive Function Skills Your Child Needs in the Age of Attention. Reprinted here with the permission of author Michael Delman.

Your Kid’s Gonna Be Okay: Building the Executive Function Skills Your Child Needs in the Age of Attention book cover.

Planning . . . to Get It Done: Basic Project Management Skills

One place where having strong Executive Function skills makes people shine is in creating efficient procedures. The specific steps of a project may not be all that hard, but identifying what the steps are, the most sensible order in which to do them, how long each step will take, and how to distribute the tasks over a long period of time—that part can be very hard! These kinds of issues sapped the motivation of one of my very bright but disorganized students, preventing him from getting to the work and having the kinds of insights he normally would on a more straightforward assignment. When he said that he was planning to get the work done, he meant “wanting to,” but he didn’t mean “making and following a thought- through plan.”

To shift him from vaguely hoping to succeed to actually designing a plan, he needed the “how-to” skills that are weak in those with Executive Function challenges. The first time that we worked together on a big project, I needed to offer a great deal of scaffolding to support him and nearly continuous prompts. We used a tool we call the stm, which stands for steps, sequence, time, and mapping.62

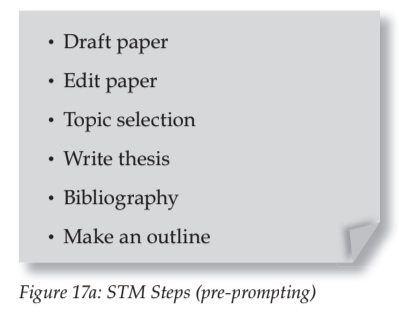

For his research paper, we created a shared Google Doc, and I had him begin by brainstorming in bullet form all of the steps he had to complete; he came up with six steps without worrying about the order. (See figure 17a.)

Then, I asked him prompting questions to get him to recall other steps that he probably knew but were not front of mind, such as, “What else could you do after drafting your thesis to see if there was enough information to write a good paper?”

He replied, “Research?”

“Sure,” I followed up. “How would you do that? Where would you go?”

He now had ten separate steps. At that point, I suggested additional steps that I thought would be worthwhile for this project, another two items for the list, and told him to include them for now and remove them later if they proved to be unnecessary. Having bulleted those steps, we then converted the bullets to numbers so that we could sequence them in a logical order, a relative strength of his. (See fi gure 17b.) He could see, for example, that it was important to draft his topic sentences—the main idea in a given paragraph— before figuring out all of the supporting details.

Next, we put in time estimates for each step, one of the hardest tasks for him. His tendency was to underestimate how long it would take to get things done. As a result, he frequently found himself tight for time, having to stay up late to complete a task and rushing to get anything done at all, producing something that would inevitably be low quality. I had twin goals to address in this challenge: first, to provide him with accurate information about how long things actually took, and, second, to increase his estimates on how long he expected things to take.

Seeing that his estimates were unrealistic, I had two choices, both of which were less than optimal: to tell him that he was mistaken and that he should agree with me about the time estimate, or to let him find out for himself that he was wrong. The former might have left him annoyed with me and less likely to take responsibility. The latter would, of course, have some negative consequences, such as a poor grade, but would also likely result in him coming up with some unrelated, but in his mind plausible, excuse for why it happened. Unfortunately, neither case would have led to much learning about why it’s important to make good time estimates and how to do so.

Instead, we came up with a range of how long things might take (See Figure 17c.) and then collected data. I encouraged him to widen the range by saying things like, “Wow! That would be really fast if you got it done in five to ten minutes. What if everything went a little bit wrong? How long might it take in that case?” While having this information might not immediately translate into more effective behaviors and better results, it began, over time, to build an awareness of how much time really was required. That awareness taught him to consider that he would need to do something differently to get better and faster results and made him a bit more open to advice.

Of course, some students, typically those who run anxious, over-estimate the time needed, sometimes to such an extent that they will not even start for fear of not being able to finish. Coming up with a range of how long a task might take and then checking how long it actually took has a dramatic effect on students in this camp as well. However, with this group, the approach is to push them to extend the low end of the time range, gently and sometimes humorously nudging them with hints that encourage pragmatism and chipping away at their defeatist perfectionism. “Yeah, it really could take two hours for that step. Actually, someone could spend five hours on it! But that would probably be going a bit overboard, right? I’m wondering how fast it could possibly be done to be ‘good enough’ for this stage, which is just a draft outline. Let’s keep two hours as the high side, but what could be the very lowest side?”

After writing down reasonable time estimates with this student, I helped him to map everything onto his planner. (See Figure 17d.) We put “DUE” on the due date and counted out the number of days he had available to get the job done. We made sure to cross off days that were not going to be workdays because of sports, family commitments, or “no-way-on-Friday” types of days. We looked at other school tasks and found the total number of days that he had at least thirty minutes available for working on the project and then added

the total time needed to complete all the steps. As we mapped the steps onto his calendar, his enthusiasm for the project grew. Now there was a way to get each step done calmly, without rushing, in a way that made it feel very likely that he would succeed. There were even “catch up” days marked with an X in case things didn’t quite work out and he needed extra help. Best of all, he could see that there was no day when the demands were beyond his capabilities.

After completing this project, we were able to apply the same process a couple months later to another project, this time with far less guidance from me. When we completed our work together, I didn’t hear from him for a year and a half, until he was midway through his first semester of college. He wanted to know how to apply the process we had used to even longer papers. We made some modifications, and after only two sessions, he again no longer needed my help. Learning to use effective tools like this improves the deployment of Executive Function skills. While planning was still not a “natural” skill for this young man, because he had learned the relevant skills, he just needed a quick booster to perform well at the new level expected of him in college.

Want to read more? Your Kid’s Gonna Be Okay is available for order through your favorite online bookstore. You can also return next week for another exclusive excerpt from the book!

Educators can help students build their Executive Function Skills, and BrainTracks can help! Learn more about BrainTracks’ school programs.

Head to our parent company’s site if you are looking for 1:1 Executive Function coaching.